Further Reading

Texas is a land of contrasts: by far the largest producer and consumer of dirty energy in the United States, yet also the largest producer of wind and solar power in the nation. We are the nation’s largest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions — eager to turn a blind eye to environmental impacts such as methane flaring, venting and fugitive emissions from oil and gas production. Yet we are the world’s pioneer of carbon sequestration and a global leader for producing clean fuels such as hydrogen. Texas operates at a global scale: the world’s 3rd largest natural gas producer behind the United States as a whole and Russia, and the world’s 6th largest wind power. Texas’s greenhouse gas emissions are on par with advanced, large economies like Germany, Canada, and South Korea.

While Texas political leaders openly dismiss and mock the risks of climate change and they act suspicious of action by policymakers in other states or countries who seek to decarbonize their economies, Texas industry, consumers and cities are decarbonizing and doing so faster than those same countries that they mock. How is it possible Texas can be so many things at once?

That’s the story of energy in Texas. It has been a 150 year-old dance with nature that has changed as new technologies are deployed, new consumer appliances are developed, and new societal expectations change.

The thread through Texas’s relationship with energy comes from a desire to make money from the land, to turn a hardscrabble and often barren environment into profits, and to pursue a better life. This is true whether harvesting wind with those old metal fan-like aeromotors that were used to pump water for crops and animals, or extracting oil with industrious pumpjacks, or converting the sun’s photons to electrons for the modern grid with glistening fields of shiny paneled glass.

Texas’ famous can-do spirit and pioneering attitude, together with an abundance of resources, turned this state into a global powerhouse for oil and gas extraction. We became famous for piping, refining, and consuming, for converting raw materials such as wispy gases and black tar-like petroleum from the earth into life-saving plastics, fertilizers, and medicines. We fulfilled the dreams of medieval alchemists who sought to convert worthless items like hair, straw, and lead into precious metals or other valuables. Today’s energy industry converts crude oil, which is worth less per pound than lead, into pharmaceuticals and perfumes that are worth more per ounce than gold. That same ability to make magical transformations is leading the next charge in energy: turning air and sunshine into electricity, converting water into hydrogen, and taking CO2 out of the atmosphere and sequestering it below ground.

Texas’ story of energy got us into this climate change mess. It also made us rich in the process and improved humanity. Our next chapter will get us out of this mess, help us build a better world and enrich us again.

About Michael Webber

Dr. Michael Webber holds the Josey Centennial Professorship in Energy Resources in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin and is the author of Power Trip: The Story of Energy.

We have understood the basic science of climate change for a very long time. What we are now discovering is how urgent it is to address the climate crisis and use it as an opportunity to build a better, safer, more just world.

Jeff Goodell

c. 300 BCE

Theophrastus, a student of Greek philosopher Aristotle, documents that human activity—the draining of marshes, the clearing of forests—can affect climate.

17th century

Flemish scientist Jan Baptista van Helmont discovers that carbon dioxide (CO2) is given off by burning charcoal.

18th Century

The Industrial Revolution begins, powered largely by fossil fuels.

1822

French mathematician Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier suggests something in the atmosphere is keeping the world warmer than it would otherwise be, a hint at the greenhouse effect.

1840

Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz presents evidence of past changes in Alpine glaciers pointing to ancient Ice Ages and showing that the climate has not always been stable.

1856

American scientist Eunice Foote discovers that CO2 absorbs heat.

1896

Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius constructs the first model of the influence of atmospheric CO2 on climate.

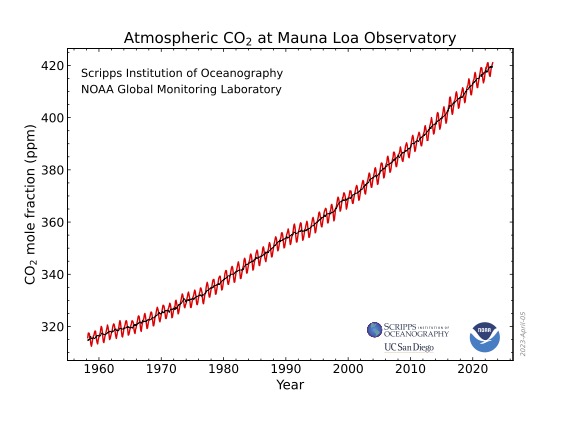

1958

American scientist Charles David Keeling begins to track atmospheric CO2 concentrations atop Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii. Those measurements are still being taken today, creating a long-running and precise record of CO2 levels in the atmosphere.

1963

The Conservation Foundation hosts the first meeting of experts concerned with climate change. Their report warns that a rise in sea level is likely, including “immense flooding” of shorelines.

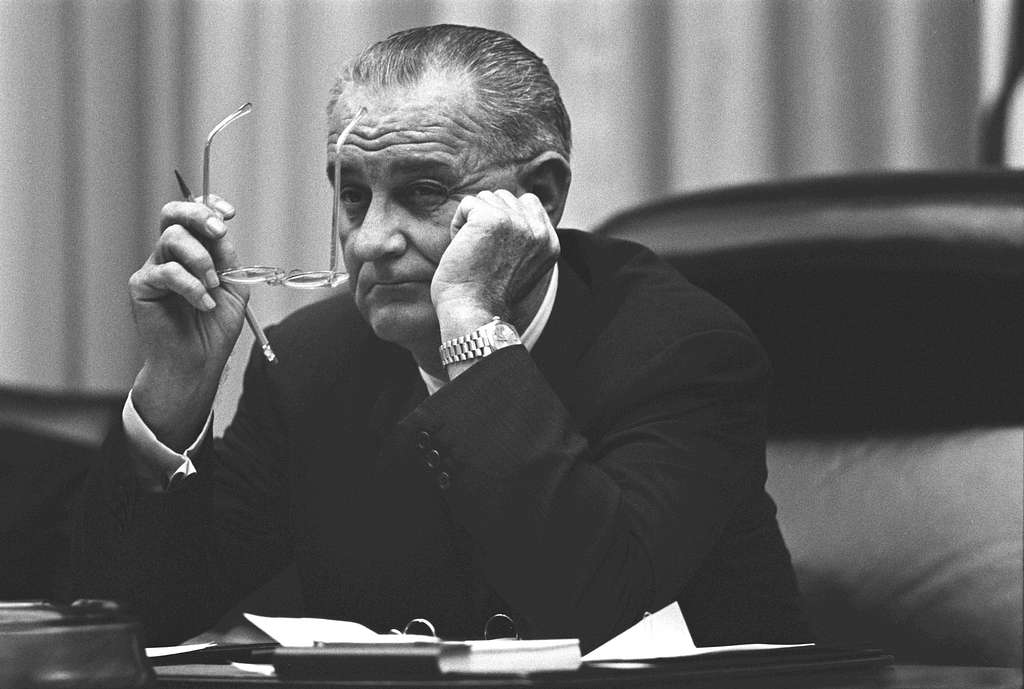

1965

Scientists write a memo to President Lyndon B. Johnson about climate change, warning him about the dangers of increasing levels of CO2 in the atmosphere due to burning of fossil fuels.

1977

ExxonMobil begins modeling the climate impacts of CO2 released by burning fossil fuels. These early models accurately predicted atmospheric warming in the decades since.

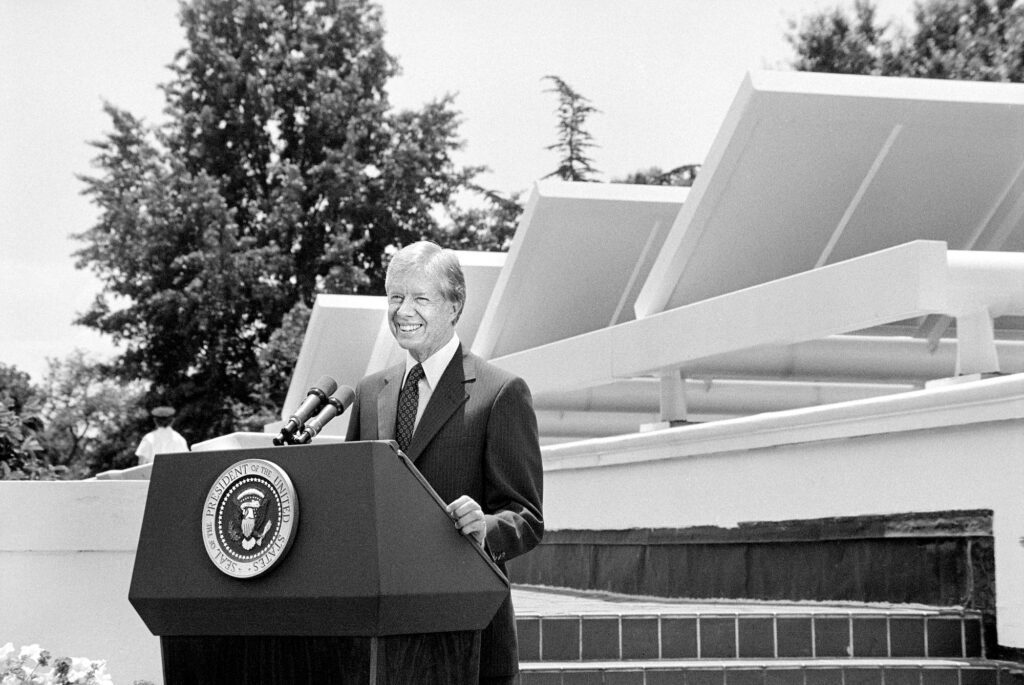

1979

President Jimmy Carter installs 32 solar panels on the roof of the White House, calling the transition to clean energy “just a small part of one of the greatest and most exciting adventures ever undertaken by the American people.” Seven years later, President Ronald Reagan removed the solar panels.

1988

NASA scientist James Hansen testifies before Congress, announcing that “the human fingerprint of global warming” has been detected.

1990

The first report by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change notes the world has been warming and future warming seems likely.

1992

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro creates the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change.

1996

General Motors introduces the EV1, the first mass-produced electric car. The car receives positive reviews and is well-received by consumers. Nevertheless, GM stopped production in 2002 and took back all cars under lease and crushed them.

1997

The U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change creates the Kyoto Protocol with the intent to limit greenhouse gas emissions from industrialized countries. The United States, the largest emitter at the time, does not sign on.

2006

Al Gore’s climate change film, An Inconvenient Truth, is released. The film was a box office success and won numerous awards, including the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

2007

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states it is “very likely” (at least 90 percent certain) that humans are responsible for most of the observed warming trends of the past 50 years. It also says warming of the planet is “unequivocal.”

2009

The U.S. House of Representatives passes the American Clean Energy and Security Act to establish a cap-and-trade system for limiting carbon dioxide emissions. The U.S. Senate fails to vote on the bill, securing its failure.

2015

The Paris Agreement (which replaces the Kyoto Protocol) is adopted by nearly 200 countries, including the United States. The central goal of the agreement is to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” To achieve the 1.5°C goal, the agreement stated that greenhouse gas emissions must stop growing before 2025 and decline 43% by 2030. Today, it’s clear that nations of the world are unlikely to meet those targets.

2021

The sixth Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report warns unequivocally that human activity has brought widespread and rapid changes to the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere.

2022

“Greenhouse gas emissions keep growing, global temperatures keep rising, and our planet is fast approaching tipping points that will make climate chaos irreversible,” United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres says at the U.N. climate summit in Egypt. “We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator.”

2023

The International Energy Agency projects that global investment in clean energy – from wind, solar, and other non-fossil fuel sources – will surpass $1.7 trillion this year. For the first time, the agency says, global investment in solar will eclipse investment in oil production. In virtually every part of the world, electricity created by clean energy is cheaper than electricity created by fossil fuels.

World Meteorological Organization announces that the past eight years were the warmest ever recorded in human history. Global temperatures, WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalassays says, are headed into “uncharted territory.”

Publications

Many of these publications are available for purchase from our Museum Store and at most major retailers / bookstores. A selection of these books will also be available to read in the exhibition resource area, located on the mezzanine of the museum.

Amitav Ghosh

The Great Derangement: Fiction, History, and Politics in the Age of Global Warming, University of Chicago Press, 2016

The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis, University of Chicago Press, 2022

Jeff Goodell

The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World, Little, Brown and Company, 2017

The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet, Little, Brown and Company, 2023

Katharine Hayhoe

Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World, Atria/One Signal Publishers, 2021

Downscaling Techniques for High-Resolution Climate Projections: From Global Change to Local Impacts, Cambridge University Press, 2021

Elizabeth Kolbert

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, Picador, 2015 (Paperback)

Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future, Crown, 2022

Sy Montgomery

The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness, Atria Books, 2016 (paperback)

How to Be a Good Creature, Mariner Books, 2018

Of Time and Turtles: Mending the World, Shell by Shattered Shell, Mariner Books, 2023

Olufemi Taiwo

Reconsidering Reparations, Oxford University Press, USA, 2022

John Vaillant

The Golden Spruce: A True Story of Myth, Madness, and Greed, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006

Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World, Knopf, 2023

Michael Webber

Power Trip: The Story of Energy, Basic Books, 2019

Thirst for Power: Energy, Water, and Human Survival, Yale University Press, 2018

Amy Westervelt

Essays for All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis, ed. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson, Penguin Random House, 2021

For Younger Readers

Joanna Cole

The Magic School Bus and the Climate Challenge, Scholastic Inc., 2014

Carole Lindstrom

We Are Water Protectors, Roaring Brook Press, 2020

David Miles

Climate Change, the Choice Is Ours: The Facts, Our Future, and Why There’s Hope!, Bushel & Peck Books, 2020

Sy Montgomery

Becoming a Good Creature, Clarion Books, 2020

Eddie Reynolds

Understanding Climate Crisis, Usborne, 2019

UT Faculty & University Educator Support

If you would like to explore ways to engage student audiences through this exhibition, our Education team are available to discuss class preparation and other learning opportunities.

Ray Williams

Director of Education and Academic Affairs

ray.williams@blantonmuseum.org

Siobhán McCusker

Museum Education, University Audiences

siobhan.mccusker@blantonmuseum.org